Everyday Abolition: A Conversation with Professor Lamble & Dalton Harrison

For my researcher development trip, I visited Abolitionist Futures co-founder and organiser Sarah Lamble, Prof of criminology and queer theory at Birkbeck College.

The busy streets of London echoed with anticipation at each footstep as I walked around the corner to reach Professor Lamble's office. Everywhere I looked was a mosaic of cultural dress, hums of rich languages and accents mixed with energy and action. I hesitated outside the door for a moment. Maybe switching from reading academic journals and books to meeting the person behind them made me pause. But the door swung back, and a smile appeared, and I instantly felt any nerves disappear. I was led into an office of art and books. Shelves lining the walls with books that seemed to stretch from floor to ceiling made me take a deep breath. Each poster drew me in: demanding abolition and queer and feminist action. After coffee and introductions, I was told I could call them Lamble. As we sat down to start our interview, it became an even bigger conversation than I could have ever expected.

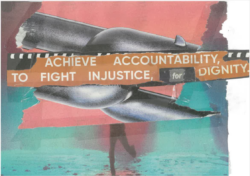

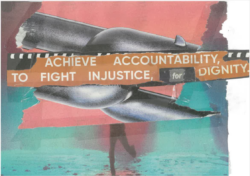

Image from arts & abolitionist futures workshop (poster created by Sarah Feinstein)

Everyday abolition

Getting all serious, I began with asking how we can start delivering acts of everyday abolition in a system such as the criminal justice system, which is historically built on control, law and order?

What followed was a really interesting conversation. Lamble said: “I am a fan of the kind of non-reformist reforms approach. We need to start building what we need outside the system so that people don’t have to use the system at all. My view is that you cannot fix the criminal justice system. I think it's unfixable. It's doing what it's designed to do, which is uphold and reinforce the existing order with its class, race and sexual hierarchies, which is the problem. So, for me, the strategies we need to use are two-pronged. One is trying to build systems and structures outside the criminal justice system that address problems and prevent people from going into the system in the first place. At the same time, we have to do things that make the system smaller and reduce its power, so that’s where we get into the idea of non-reformist reforms”.

Non-reformist reforms

I felt myself reflect on my past and as a person with a history of prison. I answered it's not something that I think about. When you're in the system, you are pushed away from thinking like that. You are almost taught there's no option; that’s the way it is, and for anyone who tries to push back on it, the system works against you, not just as a prisoner but as staff members who fight against the system and are ostracised by their peers for it. But sometimes, when you’ve been a prisoner, you can’t always see past the structure because it’s almost embedded in you.

Image is from arts and abolitionist futures workshop April 2024

Lamble acknowledged that if people were trying to fix the system from within and getting punished, were they doing something that would create genuine change, or conversely, is it the kind of change that’s like tinkering that doesn’t make the system better?

“It just reinforces the same system. I think traditionally, that’s why this distinction, which is what abolitionists called non-reformist reforms, is important. Taking a step back, there's an idea that either we abolish the prisons tomorrow or keep doing these tinkering changes, and neither of these strategies works.”

When I was in prison, another transgender prisoner handed me a copy of the Bent Bars newsletter. I felt so overwhelmed that someone was there representing our voices and cared. In University I sat reading Professor Lamble's academic work for my dissertation finally someone got it. I didn't realise until this project that Professor Lamble was the same person who had given me hope in prison and was now doing the same in their academic research to give me a voice when I was writing. This project has given me a chance to reflect, to grow academically and to understand what direction I want to take as a scholar, activist and the power of abolition.

As Lamble said in our conversation, “If you flung open all the prison doors tomorrow and let everyone out, we would still have the same issues that led people to prison in the first place. So we have to do the work of building something else.”

This is part of what we are doing with arts & abolitionist futures – working with the community in Leeds to explore how we can imagine, collectively create, and visualise the ‘something else’.

for info on the project contact ally walsh: a.m.walsh1@leeds.ac.uk

Everyday Abolition: A Conversation with Professor Lamble & Dalton Harrison

For my researcher development trip, I visited Abolitionist Futures co-founder and organiser Sarah Lamble, Prof of criminology and queer theory at Birkbeck College.

The busy streets of London echoed with anticipation at each footstep as I walked around the corner to reach Professor Lamble's office. Everywhere I looked was a mosaic of cultural dress, hums of rich languages and accents mixed with energy and action. I hesitated outside the door for a moment. Maybe switching from reading academic journals and books to meeting the person behind them made me pause. But the door swung back, and a smile appeared, and I instantly felt any nerves disappear. I was led into an office of art and books. Shelves lining the walls with books that seemed to stretch from floor to ceiling made me take a deep breath. Each poster drew me in: demanding abolition and queer and feminist action. After coffee and introductions, I was told I could call them Lamble. As we sat down to start our interview, it became an even bigger conversation than I could have ever expected.

Image from arts & abolitionist futures workshop (poster created by Sarah Feinstein)

Everyday abolition

Getting all serious, I began with asking how we can start delivering acts of everyday abolition in a system such as the criminal justice system, which is historically built on control, law and order?

What followed was a really interesting conversation. Lamble said: “I am a fan of the kind of non-reformist reforms approach. We need to start building what we need outside the system so that people don’t have to use the system at all. My view is that you cannot fix the criminal justice system. I think it's unfixable. It's doing what it's designed to do, which is uphold and reinforce the existing order with its class, race and sexual hierarchies, which is the problem. So, for me, the strategies we need to use are two-pronged. One is trying to build systems and structures outside the criminal justice system that address problems and prevent people from going into the system in the first place. At the same time, we have to do things that make the system smaller and reduce its power, so that’s where we get into the idea of non-reformist reforms”.

Non-reformist reforms

I felt myself reflect on my past and as a person with a history of prison. I answered it's not something that I think about. When you're in the system, you are pushed away from thinking like that. You are almost taught there's no option; that’s the way it is, and for anyone who tries to push back on it, the system works against you, not just as a prisoner but as staff members who fight against the system and are ostracised by their peers for it. But sometimes, when you’ve been a prisoner, you can’t always see past the structure because it’s almost embedded in you.

Image is from arts and abolitionist futures workshop April 2024

Lamble acknowledged that if people were trying to fix the system from within and getting punished, were they doing something that would create genuine change, or conversely, is it the kind of change that’s like tinkering that doesn’t make the system better?

“It just reinforces the same system. I think traditionally, that’s why this distinction, which is what abolitionists called non-reformist reforms, is important. Taking a step back, there's an idea that either we abolish the prisons tomorrow or keep doing these tinkering changes, and neither of these strategies works.”

When I was in prison, another transgender prisoner handed me a copy of the Bent Bars newsletter. I felt so overwhelmed that someone was there representing our voices and cared. In University I sat reading Professor Lamble's academic work for my dissertation finally someone got it. I didn't realise until this project that Professor Lamble was the same person who had given me hope in prison and was now doing the same in their academic research to give me a voice when I was writing. This project has given me a chance to reflect, to grow academically and to understand what direction I want to take as a scholar, activist and the power of abolition.

As Lamble said in our conversation, “If you flung open all the prison doors tomorrow and let everyone out, we would still have the same issues that led people to prison in the first place. So we have to do the work of building something else.”

This is part of what we are doing with arts & abolitionist futures – working with the community in Leeds to explore how we can imagine, collectively create, and visualise the ‘something else’.

for info on the project contact ally walsh: a.m.walsh1@leeds.ac.uk